The Conservatives did badly in the 2017 General Election and dropped several of their campaign promises, including the promise to cap certain energy bills - at least until that autumn - see further below.

Citizens Advice then drew attention to the high profits being made by the 'natural monopoly' network operators, attributing those increased profits to Ofgem's (understandable) failure to predict current low interest rates, and its (less understandable, and alleged) failure to properly investigate the capital cost of building and expanding the networks. Ofgem - probably sympathetic but reluctant or unable to re-open the current price control - responded by saying the Citizens Advice had raised some important issues which would be addressed in the next price control.

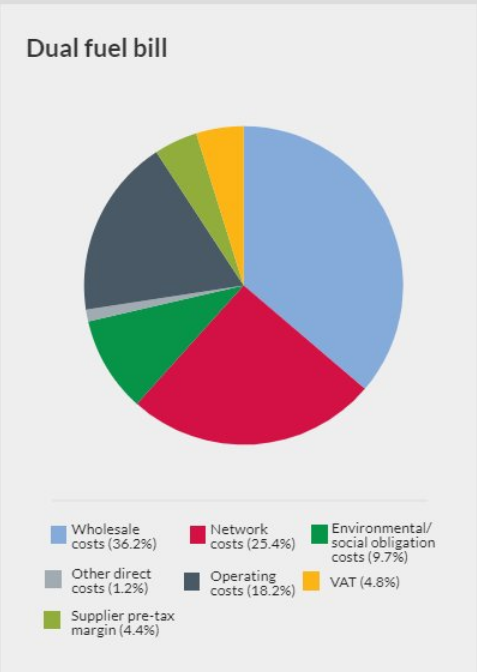

Centrica/British Gas announced a 12.5% electricity price increase in August 2017 which was met with predictable fury, despite the fact that this particular company had held prices steady since 2013. BG responded by claiming that energy policies would soon represent a larger part of an electricity bill than wholesale costs. If the carbon tax were included (and not counted as part of the wholesale price) they would hit £165 per household in 2018, up from £81 in 2014. (Other policy costs included subsidy schemes for renewables, smart metering and subsidies for conventional coal, gas and nuclear plants.) Wholesale electricity prices had fallen from £170 to £134 over the same period. This was, of course, relevant background to ....

The Helm Review

Shortly after BG's announcement, the government announced 'an independent review into the cost of energy [to be chaired by Dieter Helm] which would recommend ways to keep electricity prices as low as possible, while ensuring the UK meets its climate targets' (emphasis added). Professor Helm was quoted as saying:

'I am delighted to take on this Review. The cost of energy always matters to households and companies, and especially now in these exceptional times, with huge investment requirements to meet the decarbonisation and security challenges ahead over the next decade and beyond. Digitalisation, electric transport and smart and decentralised systems offer great opportunities. It is imperative to do all this efficiently, to minimise the burdens. Making people and companies pay excessively for policy and market inefficiencies risks undermining the objectives themselves. My review will be independent and sort out the facts from the myths about the cost of energy, and make recommendations about how to more effectively achieve the overall objectives.'

It appeared that the review would focus 100% on electricity prices (and not look at domestic gas prices). But it would not revisit the argument about price caps, instead focusing - very sensibly - on underlying cost issues. It also emerged that Professor Helm already had quite strong views about energy policy, and had been given only 30 working days in which to report. There would clearly be no opportunity for serious consultation or reflection. He was clearly expected to tell the government what it wanted and expected to hear. Whether they got it was another matter ...

Dieter Helm’s report was published in late October and clearly blamed excessive and wrong headed government intervention for high electricity prices. In an economic and regulatory tour de force, Professor Helm recommended that £100 billion of climate change costs should be isolated and charged outside regular energy bills, with industrial customers being exempt. The agricultural sector and Ofgem should be reduced in size. Here are key extracts from the report’s summary recommendations.

“This review has two main findings. The first is that the cost of energy is significantly higher than it needs to be to meet the government’s objectives and, in particular, to be consistent with the Climate Change Act (CCA) and to ensure security of supply. The second is that energy policy, regulation and market design are not fit for the purposes of the emerging low-carbon energy market, as it undergoes profound technical change.”

“The [£100 billion] legacy costs from the Renewables Obligation Certificates (ROCs), the feed-in tariffs (FiTs) and low carbon contracts for difference (CfDs) are a major contributor to rising final prices, and should be separated out, ring-fenced, and placed in a ‘legacy bank’. They should be charged separately and explicitly on customer bills. Industrial customers should be exempt. Once taken out of the market, the underlying prices should then be falling.”

“In electricity, the costs of decarbonisation are already estimated … to be around 20% of typical electricity bills. These legacy costs will amount to well over £100 billion by 2030. Much more decarbonisation [i.e. the response to climate change] could have been achieved for less; costs should be lower, and they should be falling further.”

“Government has got into the business of ‘picking winners’. Unfortunately, losers are good at picking governments, and inevitably – as in most such picking winners strategies – the results end up being vulnerable to lobbying, to the general detriment of household and industrial customers. … the government now determines the level and mix of generation to a degree not witnessed since these were determined by the nationalised industries …. Investment decision-making has been effectively quasi-renationalised.”

“The overwhelming focus on electricity rather than agriculture, buildings and transport has added to the cost. Agriculture in particular contributes 10% greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and the costs of reducing these emissions are much lower than many of the chosen options because the economic consequences of a loss of output in agriculture are small. Agriculture comprises just 0.7% GDP and at least half its output is uneconomic in the absence of subsidies. With the development of electric vehicles (EVs) it is apparent that transport can contribute more.”

“Ofgem’s role in regulation should be significantly reduced …”

“Not to implement these recommendations is likely to perpetuate the crisis mentality of the industry, and these crises are likely to get worse, challenging the security of supply, undermining the transition to electric transport, and weakening the delivery of the carbon budgets. It will continue the unnecessary high costs of the British energy system, and as a result perpetuate fuel poverty, weaken industrial competitiveness, and undermine public support for decarbonisation. We can, and should, do much better, and open up a period of falling prices as households and industry benefit from the great technological opportunities over the coming decades.”

Ministers met these challenging recommendations with complete silence.

Prices and Price Caps

But government and regulatory meddling in the energy market continued whilst Professor Helm was writing his report. Prime Minister Theresa May announced at her 2017 party conference that she would after all force Ofgem to introduce a temporary cap on single variable tariffs. It might not begin until 2019 because of pressure on the legislative timetable, and the need to consult on the detail, and would last until only 2020 unless Ofgem recommended its extension to 2023. Its introduction in the face of much sensible criticism of price caps, and its short duration, marked this out as a highly political gesture.

British Gas then announced that it would scrap its single variable tariff from April 2018, offering customers a choice of at least two three-year fixed tariffs instead. Those who did not choose one of these deals would move to a new 12 month default tariff with no exit fees. It was far from clear, of course, whether the new price structure would indeed benefit those who were unwilling or unable to take an active interest in their energy supply contracts, and if so whether this would be at the expense of those who did. The new default tariff did look suspiciously like at SVT in different clothes.

But the difficulties associated with price caps were highlighted in December 2017 when the Times reported that 'wholesale gas prices rose to their highest level since 2013 ... as a "perfect storm" of cold weather, the closure of the Forties pipeline ... and an explosion at a gas plant in Austria hit European markets'.

On the other hand ... the government announced that there would be no new cross-subsidies for clean power projects, such as tidal barrages, until 2025 at the earliest. This was to save consumers from any further increases in the annual cost of subsidies for wind, solar and nuclear power which were already costing £9bn a year. But it left the door open for targeted taxpayer support for new technologies, for instance the Swansea Bay tidal barrage. Unfortunately the projected cost of this electricity was £120 pmwh, higher even than Hinkley Point. But optimists argued that the cost of electricity generated by later schemes would be much less, once Swansea had proved the technology.

The detail of the SVT price cap was announced, subject to final consultation, in September 2018, providing savings of around 5-10% for those who did not shop around. But greater savings were of course available for those who continued (or began) to look for better deals.

There were inevitable reports of companies increasing prices very quickly before the price cap came into force. One October 2018 analysis of the 30 best annual dual-fuel tariffs found that they had risen by 21% over five months., although some of this was no doubt due to increased wholesale prices. Overall, the prices paid for all domestic fuels increased by 8.1% between September 2017 and September 2018.

But Ofgem was forced to announce an increase in the cap with effect from 2019. This was not a popular move!

Battery Capacity

Battery capacity (in cars as well as power stations) will be the key to making full use of usually-intermittent renewable generation. It was therefore interesting to read the September 2017 announcement that Drax, the country's biggest power station, intended to develop battery storage that could deliver up to 200 megawatts of power - around the same sort of output as a smaller power station. This would certainly be an impressive achievement although Drax will not yet be drawn on how long such an output might be maintained. Two or three minutes would be of no use to anyone. Two or three hours, implying usable battery capacity of 400+ MW-hours would be quite something.

There was more good news on this front when Tesla activated a 129 megawatt-hour lithium ion battery in Australia in November 2017. It is connected to a nearby wind farm and can supply 100 MW of power for around an hour thus providing very useful emergency capacity.

Change is Coming

Dermot Nolan, Ofgem's Chief Executive, made an excellent impassioned and hard-hitting speech to energy industry representatives in October 2017, warning them in particular that they faced a range of reforms including a possible rule change that would automatically switch customers to better deals. He also foresaw customers being able to have more than one supplier and so switch instantaneously from one to another. "It's a bit like allowing better deals to find customers, rather than customers having to find the deals themselves." He also drew attention to the future possibility of peer-to-peer energy trading where a householder could buy energy direct from a local power plant or electric car company.

Further pressure on larger players in the industry was highlighted by several announcements.

- A record number of customers (160,000) had switched suppliers in September 2017.

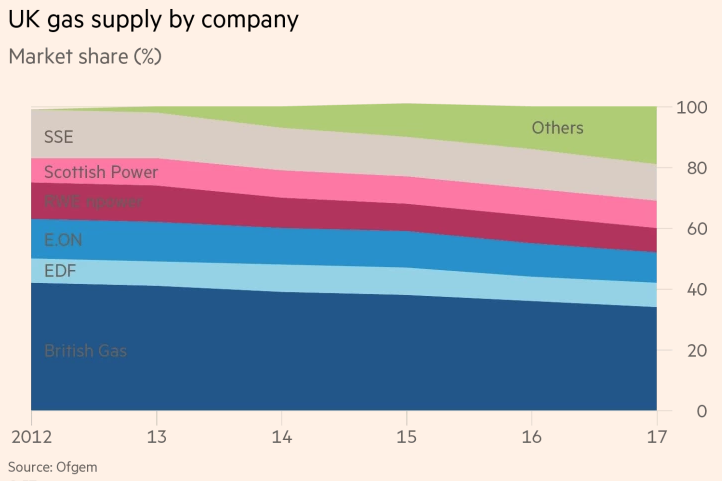

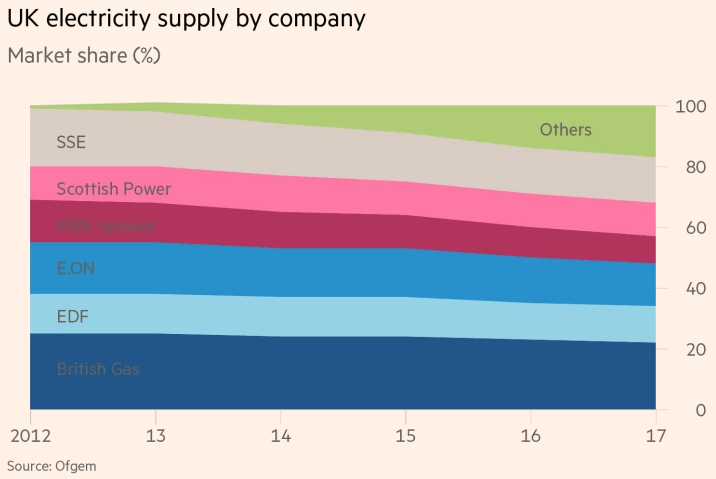

- Smaller suppliers had recently been increasing their collective share of the market by around 4% a year.

- Shares in Centrica, the owner of British Gas then fell by 15% in a single day after the company announced that it had lost 823,000 customers in four months after it had raised its prices in September.

- Royal Dutch Shell announced that it was entering the energy supply market by buying the largest challenger company, First Utility.

- Two of the big six - Innogy's npower and SSE - announced that they were to merge.

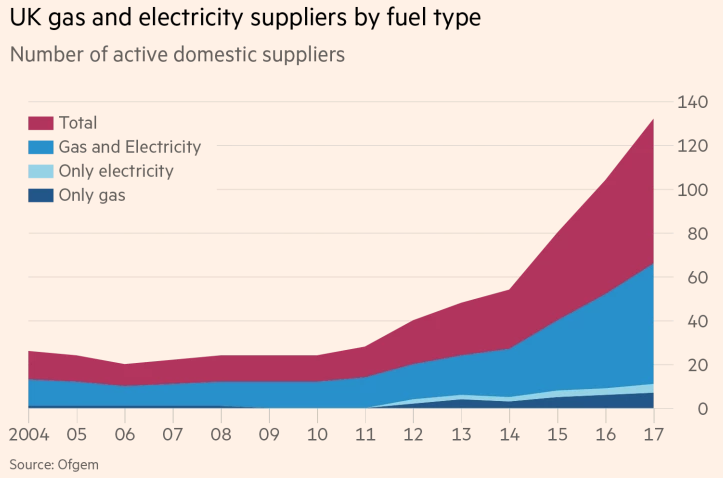

These charts nicely summarises the remarkable increase in the number of suppliers, and the slower increase in their market share:

Energy Networks

The Ofgem pie chart on the left shows the components of a typical annual dual fuel bill in 2017. Note again how the suppliers' profits (4.4%) and costs (19.4%) are dwarfed by costs outside their control, including costs specifically imposed by government - environmental obligations (9.7%) and VAT (4.8%). The total bill was £540 for gas and £577 for electricity - totalling £1,117.

Some attention was drawn in late 2017 to the high profits (included in the red segment of the pie chart) being achieved by the regulated monopolies responsible for pumping gas and distributing electricity around England and Wales, as rock bottom interest rates and other factors had enabled them to fund major investments more cheaply than had been predicted by the regulator. Click here for a further discussion of this subject.

Ofgem proposed much tougher network price controls in December 2018, to take effect from 2021.

Competition Casualties

Government and regulator encouragement had led to around 25% of the market being supplied by around 70 smaller suppliers in 2018 - a huge increase from around 2% in 2012. But some of 70 were struggling, and six went bust in the course of 2018. Ofgem did a good job in painlessly transferring their customers to other suppliers, but the surviving companies were annoyed that they had to take responsibility or for some of the failed companies' costs and liabilities.

Note

I recommend Catherine Waddams' 2018 history and analysis of energy price controls.