Economic regulation aims to correct those market failures, which are large enough to be reasonably expected to exceed those of the proposed intervention. This provides the basis for two broad schools of thought: those who put most weight on the failures of the market and have greatest faith in the positive side of the state; and those who emphasise government failures. (See note 6 below on the Harvard etc. schools of thought.)

But neither position is clearly correct. The choice is an empirical and pragmatic matter, and is likely to vary from case to case and over time too, as priorities change. Some sorts of market failure are now much more serious than others – for example, environmental externalities are of greater concern now than 20 years ago.

This web page contains notes on the main issues that arise in designing effective economic regulation.

1. Does competition policy penalise success?

2. Consumer Welfare or Rivalry?

3. Effects-based v. Form-based (or per se) Decision Making

4. What about mergers which reduce choice?

5. What about protecting competitors?

6. Harvard, Chicago & Austrian Schools

7. Intermediate Customers and Suppliers

8. Buyer Power

9. Structural v. Behavioural - including Information - Remedies

10. The use of Econometrics

11. National Champions

12. Price Matching - 'Never Knowingly Undersold'

13. Switching & Inert Customers

14. The Progressive Standard (or 'Hipster Antitrust')

15. Regulation and Competition

16. Does Competition Inhibit Sensible Cooperation?

1. Does Competition Policy Penalise Success?

"Ofcom's plans for Sky send a stark warning about the dangers of success": Daily Telegraph September 2009 quoting the Chief Executive of BSkyB. This is large companies' most frequent cry, and one cannot avoid having some sympathy with it. Take Tesco, for instance, one of the UK's best companies at deploying retail innovation, cutting costs and meeting the needs of its customers. They had grown their share of the UK grocery sales to 26% when along comes the Competition Commission (CC) and suggests that there should be a presumption against further expansion in towns etc. where they would end up with more than 60% of the local market. You can well understand their frustration, which led to their appealing what they saw as an unnecessary 'cap on growth' to the Competition Appeal Tribunal.

Equally, however, there is no doubt that aggressive behaviour - which is absolutely fine in a genuinely competitive and cut-throat market - can look (and often is) much less attractive when used by a large company to cut the throats of upstart newcomers, or others with less market power. That is why many countries have enacted abuse of dominance legislation and why the UK has gone even further and legislated for wide-ranging and powerful market investigations.

But a minority of competition economists (often known as the Chicago School - see further below) do deprecate the use of 'abuse of dominance' legislation to control the power of otherwise successful companies. And rather more economists are uncomfortable with the UK's Market Investigation legislation, as a result of which imperfections in markets can be remedied by the CC without the Commission even finding evidence of 'abuse'. They argue that the existence of such legislation only serves to deter innovation, investment and growth, and that the markets would self-correct in the longer run, if the dominant companies do indeed get flabby and complacent.

(See my Supermarkets web page for a further discussion about competition in the retail sector.)

2. Consumer Welfare or Rivalry?

Competition Authorities can in principle choose from a range of approaches when deciding whether to intervene in a market or merger.

Rivalry

UK and other EU authorities generally apply a rivalry test when assessing the benefits of otherwise of a prospective merger. Does the merger result in a substantial loss of competition? They are not required to prove that a substantial loss of rivalry will lead to harm to consumers. EU/UK legislation and jurisprudence proceeds on the basis that rivalry/competition leads to dynamism which is inevitably good, even if its direct effects cannot be measured or estimated. One advantage of this approach is that it is relatively simple to operate.

Consumer Welfare

But the rivalry test cannot be used in assessing whether there has been an abuse of dominance. Competition authorities therefore need to assess the economic consequences of restrictive agreements and other exclusionary behaviour. They usually apply a consumer welfare test - in effect asking whether the behaviour is likely to lead to consumers experiencing a detriment such as higher prices or lower quality.

Some overseas authorities, such as the Germans, nevertheless take a harder line, preferring to use something more like the rivalry test when assessing market behaviour. They are thus rather more likely to object to apparent abuse of dominance. This in turn helps preserve their 'mitttelstand' of medium sized, often family-owned, businesses.

It is more difficult to apply the consumer welfare test to mergers. This would involve carrying out a form of cost benefit analysis in which the efficiency benefits of the merger (economies of scale, head office functions etc.) are compared with the likely detrimental effects (increased prices etc.). This is a much more complex approach and so open to greater argument. Its theoretical advantages are therefore generally reckoned to be outweighed by its practical disadvantages.

Consumer welfare does, however, have a more prominent role in the USA - see this interesting 2018 article.

Total Welfare, The Citizens Interest etc.

And there is occasional quite strong pressure for a return to modern versions of the public interest test that was used in the UK for many years after World War 2.

Some companies, for instance, argue that authorities should compare the advantage to the industry following a merger against the likely detriment to the consumer. Under this total welfare approach, higher prices etc. would be permissible if they were offset by higher company profits.

A small but growing group of 'happiness economists' and others, on the other hand, are now arguing that for a host of new factors for antitrust policy to be addressed, while also attacking 'bigness' per se. They believe that focusing on consumers overlooks other values, including vibrant small businesses, innovation, privacy, job losses and healthy democratic processes. For them, large companies by their very nature pose a unique danger to the economy and society.

Although these arguments have political attractions, competition law need not take account of these factors in order to play its part in a system promoting well-being. A law can have a narrow and immediate focus while still having broad and long-term beneficial effects. Laws against theft do not provide for an assessment of the well-being or welfare effects of transferring property from its original owner to the thief (indeed, they might be less effective in promoting societal well-being if they did). Any law is part of a system of laws, so competition law does not need to do everything.

There is also the point that “If you chase two rabbits, you will catch neither one” - a lesson that applies just as strongly here as it does in the case of other areas of regulation.

A 2018 paper by John Davies analyses these arguments in a very interesting and accessible way.

3. Effects-based v. Form-based Decision Making

Legislators and competition authorities can in principle also choose between two quite different approaches to deciding whether particular activity is illegal. The form-based approach requires the regulator to do no more than to look at the behaviour of a company and decide whether it is inherently or intrinsically illegal. (Lawyers talk about behaviour being illegal 'per se'.) Secret price fixing cartels clearly fall into this category. But this approach does generally require there to be clear threshold criteria for illegality, and these can be hard to define. UK competition law for instance, once contained complex restrictive trade practices legislation, with its own court, but this became unworkable. There has therefore been a general trend in Europe for authorities instead to examine the economic effects of potentially anti-competitive behaviour. This alternative approach is called 'effects based' or 'economics based' decision making and this is now generally preferred at least in most abuse of dominance cases as well as merger control.

Within Europe, the Germans continue to favour form-based decision-making rather more than do other member states. German merger control laws, for instance, have clearer (and tighter) limits than those of other member states. The Americans, in contrast prefer to avoid approaches which, in a sense, assume illegality in certain circumstances.

But one big attraction of the form-based approach is speed of operation, allowing ex ante (before the event, or prohibitive) action, rather than relying on ex post (after the event) action which allows maybe irreparable damage to be done before time-consuming analysis begins (often impeded by information asymmetry) and eventual decision and punishment. This choice is accordingly part of the ex ante v. ex post debate within the wider debate about the ineffectiveness of much regulation.

4. What about mergers which reduce choice?

UK competition policy does not protect societies against mergers which reduce consumer choice (and hence reduce total welfare) without reducing rivalry. Two examples help illustrate this point.

Imagine a town in which a mainstream supermarket is competing with a (somewhat down-market) discounter (a sort of local Aldi or Lidl) - or with a local upmarket rival along the lines of Waitrose. Is there any objection to the Aldi/Lidl/Waitrose store being acquired by Tesco or Sainsbury's - a more direct competitor to the existing mainstream supermarket? The answer, in UK law, is an emphatic "no" as the net result is a clear increase in rivalry now that the two stores are competing head to head. But the inhabitants of the town are unlikely to see it the same way, for their breadth of choice has clearly been reduced.

Alternatively, what if the Aldi/Lidl/Waitrose business were to be acquired by a clothes retailer? Again, although customers clearly now have much less choice of where to shop for food, the merger of a clothes store and a food store does not reduce competition between those stores (for there was none) and so the merger would be allowed.

5. What about protecting competitors?

Competition policies and legislation do not provide any protection for competitors, such as smaller firms. As long as there is sufficient competition for customers' business, the health of any particular competitor, or group of competitors is immaterial. In particular, competition authorities do not protect small firms against effective (and perhaps business fatal) competition from larger firms, as long as those firms are not abusing their dominant position.

Indeed, some competition practitioners regard competitors' complaints about potential mergers to be a very good sign that the competitors fear more intense competition which would be good for consumers. Put another way, a more oligopolistic post-merger market structure should be good for all the companies in the market, as prices of all companies will tend to drift upwards as they collectively assert their market power.

This scepticism about competitors complaints may well be justified in the case of, say, Virgin Atlantic expressing concern about a merger between two other airlines. In practice, however, competitors may have real concerns about a newly merged, more powerful competitor abusing its dominant position in ways which just fall under the competition authorities' radar, or which the authorities are powerless (or do not have the resources) to attack. Given the fairly lamentable track record in progressing abuse cases, such concern is presumably often justified. I understand that some of the mobile phone companies are objecting to the proposed Orange/TMobile merger on the grounds that it will slow down the pace of innovation across the industry.

6. Harvard, Chicago & Austrian Schools

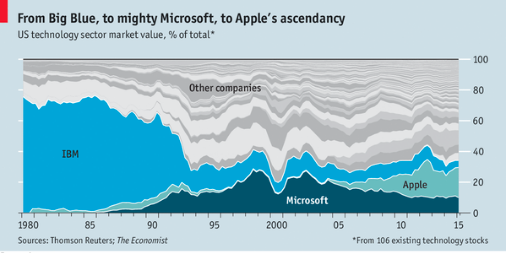

Competition policy debates often tend to resolve into disputes between those who favour intervention (the Harvard School of economists) and those who have greater belief in the long-run efficiency of markets and are relatively sceptical about the effectiveness of government intervention and regulation (the Austrian and Chicago Schools). The latter are more likely to believe that competition will erode high profit margins and that markets may be contestable if not actually currently contested. (In other words, they believe that apparently powerful companies will often not exploit their market power for fear of being taken by surprise by a new entrant.) Their favourite chart, showing the successive overturnings of the power of IBM and Microsoft, is on the right.

Competition policy debates often tend to resolve into disputes between those who favour intervention (the Harvard School of economists) and those who have greater belief in the long-run efficiency of markets and are relatively sceptical about the effectiveness of government intervention and regulation (the Austrian and Chicago Schools). The latter are more likely to believe that competition will erode high profit margins and that markets may be contestable if not actually currently contested. (In other words, they believe that apparently powerful companies will often not exploit their market power for fear of being taken by surprise by a new entrant.) Their favourite chart, showing the successive overturnings of the power of IBM and Microsoft, is on the right.

Chicago/Austrian School economists still object to hard core cartels, and mergers which create monopolies, but are sceptical that apparently predatory behaviour does any harm, and contend that most oligopolies and tacit collusion do very little harm.

There is these days relatively little support for pure Chicago/Austrian School economics, but there is also a good deal of concern that regulatory interventions can all too easily lead to unintended consequences. Most competition authorities therefore sit somewhere between the extremes characterised by the two schools of thought, and increasingly employ econometrics and game theory to analyse potentially problematic behaviour.

Andrei Shleifer has analysed these competing arguments very well.

7. Intermediate Customers and Suppliers

Many companies do not supply the final consumer but instead supply goods and services to manufacturers, retailers etc. A pure consumer welfare test would perhaps permit most mergers between such companies, especially where the intermediate customers - such as large supermarkets - are relatively powerful (in other words, they have strong buyer power - see further below). In practice, however, there is a strong presumption, at least in the UK, that mergers that substantially reduce competition between intermediate suppliers will eventually result in harm to consumers.

8. Buyer Power

A company (or small number of companies) has strong 'buyer power' if it/they can resist price rises that would otherwise be imposed by a supplier (or suppliers) with market power. The large supermarket chains, for instance, are reckoned to have sufficient buyer power to be able to impose quite tough deals on even their largest and most powerful suppliers. Buyer power is therefore generally regarded as a good thing, as long as the benefits are passed on to the final consumer - which depends on the companies with buyer power themselves operating in a competitive market. Unfortunately, however, companies that are so large that they have significant buyer power are also sometimes large enough to have significant market power when they are selling their products. They therefore make large profits by buying at lower prices and selling at higher prices than would be possible in a truly competitive market.

9. Structural v. Behavioural - including Information - Remedies

It is surprisingly difficult to identify how best to remedy the consequences of an unattractive merger, and so avoid simply prohibiting it. And it is equally difficult to identify the best way to avoid consumers being ripped off. These issues are discussed in a separate web page.

10. The use of Econometrics

The vastly increased availability of data from companies' (such as supermarkets') IT systems plus the increased power of competition authorities' own computer systems mean that attempts are now often made to model companies behaviour so as demonstrate certain behaviours and correlations. But the models and spreadsheets have to be transparent and audit-able (not least by the companies under investigation) and easily explained to business people affected by regulatory decisions, and also to non-economist judges in court actions and appeals. (Correlation does not prove causality, for instance.) This severely limits the use of the more complex models.

11. National Champions

There is no inherent tension between industrial policy and competition policy. Both (or at least both should) result in more efficient, innovative and therefore rapidly growing businesses. But there can be some tension between (a) those who want to create 'national champion' businesses by encouraging firms to merge, and (b) competition authorities who generally resist mergers which substantially reduce domestic competition. This interesting and important subject is explored at pp 37- in the collection of the late Professor Geroski's Essays in Competition Policy.

The protection of nationally important UK companies from being taken over by foreign 'predators' on public interest grounds is discussed here.

An interesting 2018 case was the proposed merger between Siemens' and Alstom's railway businesses. It was on the face of it a clear candidate for prohibition by the EU Commission - and it was indeed duly prohibited in early 2019 - but the companies, backed by Chancellor Merkel and President Macron, argued that we needed a European champion to compete effectively with China's CRRC which benefits from huge Chinese government support and preference.

Several distinguished academics wrote this open letter in connection with the case:

More, not less, competition is needed in Europe :- We have been looking with preoccupation at the political pressure on the European Commission in the context of the merger between Siemens and Alstom, and even more at the political reactions to the prohibition decision. In particular, the announcement of possible initiatives by the French and German governments to relax European competition policy so as to favour mergers among large European companies is extremely worrying. Competition policy should be independent from political interference based on perceived European industrial goals, and respond to efficiency considerations and the protection of the competitive process.

The argument that it is sufficient for two firms to merge and increase in size to become more competitive in the international markets is fallacious. Siemens and Alstom are already leading firms in the international markets, and as such already benefit from important economies of scale and scope. We have not found in the public domain any explanation of why their union should give rise to significant efficiency gains (and the European Commission states in its press release that the companies have not substantiated any such efficiency claims).

Absent efficiencies from the merger, the elimination of competition between Siemens and Alstom may well increase profits, but it would make the merged firm less competitive in international markets and harm its customers, such as train operators and rail infrastructure managers, which will likely have to pay higher prices and enjoy less innovation and quality, and ultimately final consumers. Unsurprisingly, customers have strongly opposed the transaction (had Siemens become more competitive after controlling Alstom, actual and prospective buyers would have been the first to welcome the merger).

Competition law provisions do not prevent the formation of national or European champions, as long as a merger brings about sufficiently strong synergies and complementarities between the merging parties. Indeed, the European Commission prohibits mergers only in rare occasions, when the predicted anti-competitive effects for buyers and consumers are significant and no compensating efficiency gains are likely.

If anything, the mounting empirical evidence on increased market power and concentration call for stronger competition enforcement, responding only to impartial efficiency criteria and not to political opportunism. Europe needs more efficient, competitive, and innovative firms. Sponsoring mergers which remove competition would achieve the opposite.

Massimo Motta (ICREA-Universitat Pompeu Fabra and Barcelona GSE) Martin Peitz (University of Mannheim and MaCCI) & c.50 others

12. Price Matching - 'Never Knowingly Undersold'

Competition Authorities are in a bit of a bind when it comes to investigating price promises and the like. Many customers would not use Expedia, Booking.com and similar websites unless they promise that they offer rooms etc. at the same price (or lower) than if you book direct with the hotel, or via another website. But these Most Favoured Customer (MFC) agreements are fundamentally anti-competitive as they deter any competition between websites and/or between websites and the hotels. Such agreements between websites and hotels have accordingly been ruled to be illegal as a form of cartel. Unfortunately, the result has been to encourage a switch to unilateral promises that the vendor will match a lower price offered by a competitor. (John Lewis, in the UK, is famous for its pledge that it is never knowingly undersold, a rather clunky way of making the same promise.) The obvious highly anti-competitive result is that no-one bothers to compete with the person making the promise, thus ensuring that the customer is denied the opportunity to save money by shopping around. This could in theory be attacked as an abuse of dominant position, but most if not all companies making these promises are not dominant in their market.

An interesting and relatively readable analysis of the law and practice in this area has been published by the Centre for Competition Policy. You can read it here.

(The MFC phrase/acronym is by analogy with Most Favoured Nation (MFN) clauses in trade agreements whereby one country is prohibited from offering lower tariffs to other countries.)

13. Switching & Inert Customers

See separate webpage here.

14. The Progressive Standard (aka Hipster Antitrust)

Pressure grows, from time to time, for competition authorities to worry about much more than just rivalry or consumer welfare (see '2' above). For a further discussion of this issue it is worth reading 'Antitrust in the Tech Sector' - a speech by Senator Orrin Hatch who counters calls for the traditional consumer welfare approach to be replaced by a more progressive standard - described by a competition expert as 'hipster antitrust'! Senator Hatch describes the various calls as follows:- "Many in the media call for antitrust to pursue everything from industrial democracy to campaign finance reform to material levelling. Above all else, we hear again the old, lazy mantras that big is bad, disruption is suspect, and public utility designation is welcome."

There are of course perfectly good cases to be made for laws and regulations which encourage industrial democracy and the like. But they should be debated and if appropriate developed separately, and not merely added to the duties of competition authorities who have a hard enough job to do without asking them also to pursue a range of quite unrelated goals.

15. Regulation and Competition

There is understandable concern that well-intended regulation might accidentally damage competition and hence increase prices, reduce quality, and reduce the pace of innovation. This issue was discussed in a detailed 2020 report by the Competition and Markets Authority .It made a number of points including:

- the need to guard against regulations which serve firms - and especially incumbent firms - with vested interests.

- a recommendation that policy makers should increase their focus on competition and innovation when assessing regulatory interventions.

16. Does Competition Inhibit Sensible Cooperation?

The short answer is 'yes'. The trouble is that cooperation that is apparently in the interest of customers can very quickly morph into standardization which leads to less intense competition and less innovation etc. Here are some random thoughts and examples.

- Airlines do not cooperate when there is travel disruption. Passengers can suffer very badly as a result. I am not sure why they do not cooperate more effectively at such times.

- A bid to standardise the ramps used to help disabled passengers board different types of train failed because one company thought this anti-competitive. As a result, much time can be lost at stations served by more than one train company as platform staff struggle to find the right equipment and get it to the right place.

- Supermarkets are not allowed to collaborate to increase the price of alcohol, for instance, despite the health benefits likely to accrue from such a policy.

- The CMA announced that no enforcement action would be taken against businesses cooperating so as to reduce damage to consumers and others during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Further detail is in a note by Tasneem Azad.